If you do reflect upon it, nothing lasts forever...

Sometimes a love ends,

sometimes a friendship fades away...

How many bonds can deteriorate.

But cut a lock of hair to the person you love,

and it will keep its color, her light for decades,

indeed, even for centuries.

The Victorians taught us that. In fact, the art of working human hair, one of the many traditions of the XIXth century, has come down to us as if it had remained frozen in time. And My Little Old World has already mentioned it to you by discussing, some time ago, the importance that, in the collective imagination, female hair had in the Victorian era, so much so that, if their robustness allowed it, they were not cut for a whole life.

Back then, locks of hair were wisely woven into jewels, wrapped around themselves to resemble flower petals, even ground to be used in pigments and what we find ourselves today to confront with are authentic masterpieces made to defeat the laws of existence. The hair of a loved one, and who had been lost, was preserved as a memento mori already during the Shakespearean period and probably from well before eras. In fact, in some Egyptian tombs there are frescoes that seem to represent scenes in which pharaohs and queens exchange locks of hair as a sign of love. From 1600-1700 a sort of cult, aimed at preserving the memory of deceased loved ones, began: at that time infant mortality was very high, but also that of adults reached exorbitant numbers. And making personal objects, especially jewelry, with locks of their hair, gradually became a custom. But in the Victorian era, this art, which became more and more widespread and practiced, was mainly aimed at making paintings with family trees, objects to be exchanged as a token of love or friendship, frames for portraits, etc. using the hair of people who were still alive. It was not unusual that to be wowen were hair of different colors because it belonged to different people, perhaps united by a family bond: for example, a gift given to a father by three daughters of his. It could also have been a simple bookmark, but to insert it in a journal assumed the meaning of having with you the true essence of who had donated that hair. In the image below, a tree represents an American Methodist congregation: the shoots covering the branches are made with the hair of each member who was part of it.

From the collection of John Whitenight and Frederick LaValley. Photo by Alan Kolc. Courtesy of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia and the Mütter Museum

And here they are some other jewels and a framed drawing to hang to a wall belonging to private collections.

It is likely that they were, above all, the Victorian ladies who devote themselves to this art, which today appears so unusual to us and which reached the peak of its diffusion around 1850; probably it was a parlor pastime, as it was making wax flowers (click HERE to read the post that My Little Old World dedicated to this topic), to embroider, to sew, to create photocollages (click HERE to read the post that My Little Old World dedicated to this topic). But among all the artistic works mentioned, the one who worked human hair was certainly the most particular, that which required much skillness and that only high-ranking people could afford: not everybody could buy what it was needed and, let's remember it, many were the women who had to work to support their families and certainly they had no way to think about leisure.

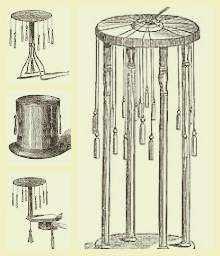

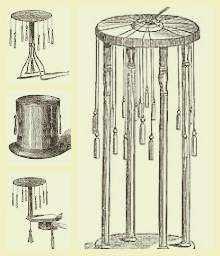

To wrap the strands of hair it was necessary to have a working table with a circular base that had to meet certain requirements. In reality there were several types of braiding tables: one was made in the shape of a pouf and was named ladies' table; it could be used while seated, but often cluttered to the point of hindering the lady who was sitting beside. The other had longer legs and was a full-fledged perch table, but it was more inconvenient to work on it because you had to lean forward. There was still another, the smallest one, which had to be anchored to a side of a table. But there were also those ladies who were clever enough to simply use an inverted cylindrical container, or a hat, on the bottom of which, in the center, they had made a hole; various pieces of twine branched off from it as many as they were required by the pattern they'd chosen, and the strands were tied to them. At the head of each piece of twine they were tied wooden shuttles or lead weights to use them easily. Finally, special patterns, collected in catalogs or manuals, were a valid help to create these very complex artistic objects. The image below represents the cover of the best known, and probably most used one, dating back to 1870.

A. Bernhard & Co. Catalogue, 1870 Manufacturers of Diamond Work & Ornamental Hair Jewelry importers of German Jewelry, Watches, Diamonds, etc.etc.

169 Broadway, Gilsey Building, Rm. 3 New York

But the more sophisticated families and the less industrious ladies went to real artisans who had handed down this art for generations. Unfortunately the names of the various artists have not reached us and all the works that have been preserved are anonymous.The first thing to do was to prepare the hair strands by properly cleansing them following some instructions with much care. The following are taken from a 1850s serie of issues of The Godey’s Lady’s Book:

“Sort the tress, which is about to be used, into lengths, tie the ends firmly and quite straight with pack thread, put the hair into a small saucepan with about a pint and a half of water, and a piece of soda of the size of a nut, and boil it for a quarter of an hour or twenty minutes; take it out, shake off the superfluous moisture, and hang it up to dry, but not near a fire.”

“When it has become perfectly dry, divide it into strands containing from twenty to thirty hairs each, according to the fineness of the hair or the directions given for the pattern about to be worked. It must be observed that every hair in the strand should be of the same length, and the strands should be all of an equal length.”

"Knot each end of each strand, then take the requisite number of leaden weights, weighing about three quarters or half an ounce each, and affix about a quarter of a yard of pack thread to each of them; lay them down side by side on the table, and to the other ends of the pack thread affix the strands of hair already prepared, knotting them on with a weaver's or sailor's knot; care must be taken all this time to prevent any entanglement or derangement of the hair."

"The other ends of the strands must now be gathered together, firmly tied with pack thread, and then gummed with a cement composed of equal parts of yellow wax and shellac melted together and well amalgamated, and then rolled into sticks for use. We now come to the table and the arrangement of the strands on it."

And thus had come the time to proceed following the creativity or the chosen models, letting oneself be guided by the patterns.

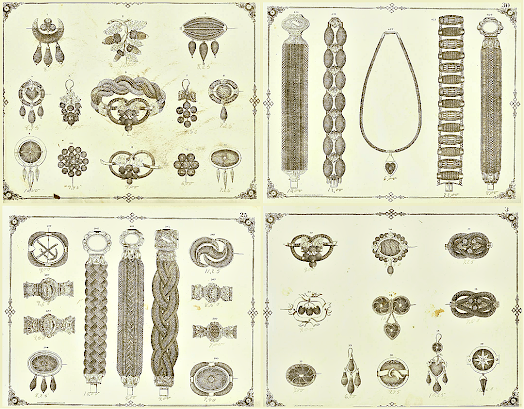

Here you are some pages from the A. Bernhard & Co. Catalogue, 1870 Manufacturers of Diamond Work & Ornamental Hair Jewelry representing some models of jewels or small keepsakes in hair

I don't go into the descriptive details of every single pattern because they look like real puzzles just reading them; I limit myself to publishing some images and just the starting indications, always taken from the same issues of The Godey's Lady's Book, so that you can at least realize what these ladies of ours were capable of:

A PATTERN FOR A BRACELET (Fig. 4.)

"Sixteen strands of twenty-five or thirty hairs each, according to the fineness of the hair. For this pattern the strands must be arranged in fours, and numbered."

CHAIN OR GUARD PATTERN (Fig. 6.)

"Ten strands only, of about twenty hairs each, are required for this. They must be arranged thus."

A PATTERN FOR A CHAIN OR A GUARD (Fig. 2.)

"For this pattern, sixteen strands, each consisting of about twenty hairs, are required. These must be arranged in pairs on the circle on the table, at equal distances, and so that the opposite pairs shall be in direct lines with each other."

And I'm stopping here, Victorian ladies were much more patient and ingenious than us, that's sure! But it must be said that they could afford to devote much more time to leisure than we can dedicate to it today, perhaps this is what we lack most, alas!

Thanking you with all my heart for following me up to here,

I'm giving you an appointment at the next post,

while sending you much love.

See you soon ❤

LE OPERE D'ARTE REALIZZATE DALLE LADIES VITTORIANE: Gioielli creati con capelli veri

IMMAGINE 1 - Orecchini fatti con capelli veri montati su oro

Se ci pensate bene, nulla dura per sempre...

Talvolta finisce un amore,

talvolta si logora un'amicizia...

Quanti legami possono deteriorarsi.

Ma tagliate una ciocca di capelli alla persona che avete cara,

ed essa manterrà il suo colore, la sua luce per decenni,

anzi, persino per secoli.

Ce lo hanno insegnato i Vittoriani. Infatti l'arte che lavorava capelli umani, una delle numerose tradizioni del XIX° secolo, è giunta fino a noi come fosse rimasta congelata nel tempo. E My Little Old World ve ne ha già fatto cenno trattando, tempo fa, dell'importanza che, nell'immaginario collettivo, avevano, in epoca vittoriana, i capelli femminili tanto che, se la loro robustezza lo consentiva, non si tagliavano per una vita intera.

IMMAGINE 2 - Lady vittoriana con la sua lunga chioma

A quel tempo ciocche di capelli venivano sapientemente intrecciate in gioielli, avvolte su sé stesse per assomigliare a petali di fiori, persino macinate per essere utilizzate in pigmenti e ciò con cui ci troviamo a confrontarci oggi sono autentici capolavori realizzati per sconfiggere le leggi dell'esistenza. I capelli di una persona amata, e che si era perduta, erano conservati come memento mori già a partire dal periodo shakespeariano e probabilmente da epoche ben antecedenti. In alcune tombe egizie si trovano, infatti, affreschi che sembrano rappresentare scene in cui faraoni e regine si scambiano ciocche di capelli in segno d'amore. Dal 1600-1700 prese avvio una sorta di culto volto a preservare il ricordo dei cari deceduti: allora era altissima la mortalità infantile, ma anche quella degli adulti raggiungeva cifre esorbitanti. E fabbricare oggetti personali, soprattutto gioielli, con ciocche della loro chioma, divenne a poco a poco una consuetudine. Ma in epoca vittoriana, questa arte che divenne sempre più diffusa e praticata, era più che altro volta a fabbricare quadri con alberi genealogici, a confezionare oggetti da scambiare come pegno d'amore o d'amicizia, ad incorniciare ritratti, etc. utilizzando chiome di persone ancora in vita. Non era inusuale che venissero intrecciati capelli di colori differenti perché appartenenti a persone diverse, magari unite da un legame di parentela: per esempio un dono fatto ad un padre da tre figlie. Poteva anche trattarsi di un semplice segnalibro, ma inserirlo in un diario personale assumeva il significato di avere con sé la vera essenza di chi aveva donato quei capelli. Nell'immagine qui sotto un albero rappresenta una congregazione metodista americana: i germogli che ne rivestono i rami sono fatti con i capelli di ciascun membro che ne faceva parte.

IMMAGINE 3 - Dalla collezione di John Whitenight e Frederick LaValley. Fotografia di Alan Kolc. Courtesy of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia and the Mütter Museum

Ed eccovi altri monili ed un disegno incorniciato e da conservare appeso ad una parete come ornamento che fanno parte di collezioni amatoriali.

IMMAGINI 4-5-6-7-8-9

Si suppone che a dedicarsi a quest'arte, che oggi ci appare così inconsueta e che raggiunse il culmine della sua diffusione attorno al 1850, fossero soprattutto le ladies vittoriane e che si trattasse di un passatempo da salotto, così come lo erano fabbricare fiori di cera (clicca QUI per leggere il post che all'argomento ha dedicato My Little Old World), ricamare, cucire, creare photocollages (clicca QUI per leggere il post che all'argomento ha dedicato My Little Old World). Ma tra tutti quelli menzionati, quello che lavorava capelli umani era di sicuro il lavoro artistico più artificioso e che potevano permettersi solamente persone altolocate, non fosse altro per ciò di cui ci si doveva munire per realizzare intrecci di ogni tipo. Non tutti potevano acquistare ciò che occorreva e, ricordiamolo, molte erano le donne che dovevano lavorare per sostentare la propria famiglia e non avevano di certo modo di dedicarsi ad occupazioni dilettevoli.

IMMAGINE 10 A SINISTRA - Esempi dei vari tavoli da lavoro utilizzati per intrecciare capelli

Per avvolgere su sé stessi i capelli era necessario munirsi di un tavolino da lavoro con base circolare che doveva rispondere a determinati requisiti. In realtà ne esistevano diversi tipi: uno era fatto a forma di pouf e veniva chiamato ladies' table - tavolino per signore; poteva essere utilizzato stando seduti, ma spesso ingombrava al punto da impicciare la dama che era seduta accanto. L'altro aveva gambe più lunghe ed era un tavolino fatto a trespolo a tutti gli effetti, ma era più scomodo lavorarvi perché si doveva stare protratti in avanti. Un altro ancora, il più piccolo, veniva ancorato su di un lato di un tavolo. Ma vi era anche chi si ingegnava ed usava semplicemente un contenitore cilindrico rovesciato, o un cappello, sul cui fondo, al centro, aveva praticato un foro; da esso si diramavano i vari fili di spago, cui venivano legate le ciocche di capelli, a capo dei quali erano fissate delle navette in legno o pesi di piombo per impugnarli agevolmente. Appositi schemi erano, infine, un valido aiuto per realizzare questi oggetti artistici così tanto complessi, ed erano raccolti in cataloghi o manuali. L'immagine riportata di seguito rappresenta la copertina di quello più noto, e probabilmente il più utilizzato, risalente al 1870.

IMMAGINE 11 - A. Bernhard & Co. Catalogue, 1870 Manufacturers of Diamond Work & Ornamental Hair Jewelry importers of German Jewelry, Watches, Diamonds, etc.etc.,169 Broadway, Gilsey Building, Rm. 3 New York

Ma le famiglie più sofisticate e le ladies poco operose si rivolgevano a veri e propri artigiani che si tramandavano questa arte da generazioni. Purtroppo i nomi dei vari artisti non sono pervenuti a noi e tutte le opere che si sono conservate sono anonime.

La prima cosa da fare era preparare le ciocche di capelli detergendole adeguatamente seguendo scrupolosamente alcune istruzioni. Le seguenti sono tratte da alcuni numeri del del Godey's Lady's Book risalenti agli anni '50 del 1800:

"Separare la treccia, che sta per essere utilizzata, in lunghezze, legare le estremità saldamente e abbastanza dritte con filo da impacco, mettere i capelli in una piccola casseruola con circa mezzo litro d'acqua e un pezzo di soda della dimensione di una noce e fare bollire per un quarto d'ora o venti minuti; tirare fuori i capelli, scrollare via l'umidità superflua e appenderli ad asciugare, ma non vicino al fuoco."

"Quando saranno diventati perfettamente asciutti, dividerli in ciocche contenenti da venti a trenta capelli ciascuna, secondo la finezza del capello o le indicazioni date per il disegno da lavorare. Si deve prestare attenzione a che tutti i capelli della ciocca siano della stessa lunghezza e che le ciocche siano tutte lunghe uguali."

"Annodare ciascuna estremità di ogni ciocca, quindi prendere il numero richiesto di pesi di piombo, del peso di circa tre quarti o mezza oncia ciascuno, e attaccare circa un quarto di iarda di filo da imballaggio a ciascuno di essi; adagiarli uno accanto all'altro su di un tavolo, e alle altre estremità del filo legare le ciocche di capelli già preparate, annodandole con un nodo da tessitore o da marinaio; bisogna fare molta attenzione, durante tutte queste operazioni, al fine di evitare che i capelli si aggroviglino o si scompongano".

"Le altre estremità delle ciocche devono ora essere raccolte insieme, legate saldamente con filo da impacco, quindi gommate con una malta composta da parti uguali di cera gialla e gommalacca fuse insieme e ben amalgamate, e quindi arrotolate in bastoncini per l'uso. Raggiungere infine il tavolo da lavoro e disporre le ciocche su di esso."

Era così giunto il momento di procedere seguendo la creatività o i modelli scelti, lasciandosi guidare dagli schemi.

IMMAGINE 12 - Artigiano al lavoro

IMMAGINE 13 - Alcune pagine tratte dall' A. Bernhard & Co. Catalogue, 1870 Manufacturers of Diamond Work & Ornamental Hair Jewelry che riportano modelli cui ispirarsi per creare gioielli di ogni tipo e per tutti i gusti

Non scendo nei dettagli descrittivi di ogni singolo schema perché sembrano degli autentici rompicapo solo a leggerli; mi limito a pubblicare alcune immagini e le indicazioni di partenza, sempre tratte dai medesimi numeri del Godey's Lady's Book, perché vi rendiate almeno conto di cosa erano capaci queste nostre ladies:

SCHEMA PER UN BRACCIALETTO (IMMAGINE 14)

"Sono necessarie sedici ciocche di venticinque o trenta capelli ciascuna, a seconda della finezza dei capelli. Per questo modello le ciocche devono essere disposte a quattro e numerate."

SCHEMA PER INTRECCIARE UNA CATENA (IMMAGINE 15)

"Solo dieci ciocche, di circa venti capelli ciascuna, sono necessarie per questo schema. Devono essere disposte come illustrato dall'immagine:

SCHEMA PER UNA CATENA O UN GIROCOLLO (IMMAGINE 16)

"Per questo schema, sono necessarie sedici ciocche, ciascuna composta da circa venti capelli. Queste devono essere disposte in coppia sul piano del tavolo da lavoro, a pari distanze, e in modo che le coppie opposte siano perfettamente di rimpetto tra loro."

Ed io mi fermo qui, le ladies vittoriane erano decisamente molto più pazienti ed ingegnose di noi. Ma va detto anche che potevano permettersi di dedicare agli svaghi molto più tempo di quanto possiamo dedicarvi noi oggi, forse è questo che più ci fa difetto, purtroppo!

Ringraziandovi con tutto il cuore per avermi seguita fino a qui,

vi do appuntamento al prossimo post,

e vi auguro ogni bene.

A presto ❤

LINKING WITH:

I found the instructions for preparing the hair for the jewellery fascinating. Looking at all the patterns, it does indeed look like many puzzles. A marvellous read, dear Dany. It is lovely to visit your lovely place again and be enthralled with your research and facts.

RispondiEliminaKim,

EliminaYou’re always far welcome, Dearie, with your sweetness and your benevolence!

They are so many days I think about coming back, Suummer is such a heavy season to me, I have too much work, so I can devote to my blog just the coldest and shortest days of the year… and to come back is always such a great emotion to me!

With sincere thankfulness for your words of appreciation too,

I’m sending hugs and more hugs across the many miles ಌ•❤•ಌ

It's wonderful to see you posting again. No doubt this form of art was time consuming but most worth it to them.

RispondiEliminamessymimi,

EliminaIt's wonderful to me too to be here again and to read your so beautiful words.

For Victorian ladies it was worth to devote themselves to this kind of art, for sure!

Sending blessings to you ⊰♥Ƹ̴Ӂ̴Ʒ♥⊱

My goodness, I can't imagine having the patience to separate out strands of hair, much less such intricate patterns, and making such incredible things with the strands of hair. You tell such an amazing story. I had heard of hair ornaments and jewelry but have never seen any in real life. Thank you for sharing such an interesting post! Blessings to you!

RispondiEliminaMarilyn,

EliminaBe blessed you too!

They were required patience and skill for these works, and so much time... these are alla characteristiques that makes such artworks so precious today, we can just admire who was able and do them.

Hope you're having a great day,

I'm sending my dearest love to you ஜ♥♡♥ஜ

Can you imagine doing this? My poor fingers would be a mess -- not to mention having a scrambled brain after separating them again! You always tell us the most interesting things and I always learn something here. It's a joy when you post!

RispondiEliminaJeanie,

EliminaAnd it's a true joy to me to welcome back you here, believe me!

I so love all works needing much patience, they gratify me such a lot, but I suppose them to be too demanding to me too!

Probably if I hadn't anything else to do...

Well, in the hope you're doing well now,

I'm wishing you a most wonderful remainder of your week ⊰✽*✽⊱

So interesting to read this, many years ago I went to the museum in our town at Christmas time to see the decorations of a Victorian era home and one of the rooms had these tiny items made with hair it said and I just couldn't believe someone could work with hair and make such small items, but like you said they had more leisure time back then that we usually don't take out the time for, or to learn. Such amazing work they did!

RispondiEliminaConniecrafter,

EliminaDearest One, honestly, when I did all the researches I was able to and put together this post of mine, I felt amazed more and more coming across such handworks, so perfect to seem not to be made with human hair and by human hands!

You know, in Italy we've so many curious ancient traditons, which also requiring skill and so much time and patience too, but nothing like this one: I must say that Victorian culture, even with its oddness, is so, so charming to me... The more I study it and the more I undergo its attraction.

In the hope your week is off to a great start,

I'm sending hugs across the Ocean ∗✿≫♥≪✿∗