"Now, I believe every one has had a Christmas present and a good time. Nobody has been forgotten, not even the cat," said Mrs. Ward to her daughter, as she looked at Pobbylinda, purring on the rug, with a new ribbon round her neck and the remains of a chicken bone between her paws.

It was very late, for the Christmas-tree was stripped, the little folks abed, the baskets and bundles left at poor neighbors' doors, and everything ready for the happy day which would begin as the clock struck twelve. They were resting after their labors, while the yule log burned down...

Today I want to deal with a special topic.

I want to tell you about an authoress that we all know and have learned to love over the years through the numerous readings she left us as a legacy: Louisa May Alcott.

Her voice, like that of Charles Dickens, whom she loved and admired so much, knows no fashions, the barriers of time do not stop it and continues to resonate inexorably and to create the atmosphere of these days full of magic and profound meanings, since the passion she had for the Holiday Season really knew no bounds.

In fact, Christmas inspired her many stories, fairy tales and novels.

And it is certainly not a coincidence that her famous novel Little Women, the one that consecrated her to success, starts right from a Christmas morning, a particular Christmas, not only because it was without any gift, but because it will be loaded with truer and authentic principles that the heart of a good Christian makes its own and observes without making any effort: the love for other people, the charity, the renunciation for those who suffer, the warmth of the family are the values that most gratify our soul, especially during the Christmas period, which they give it meaning and depth more than a gift to be discarded that perhaps excites us, but the prestige of which is exhausted in something purely material.

But in reality this is not what I intended to tell to you today, or rather, it was not my intention to deal with it in this way ... I want to tell you about how Louisa May Alcott contributed to making of Christmas the real Christmas we still celebrate today.

Can you imagine a Santa Claus preparing gifts for children without the help of his faithful, hardworking and tireless goblins or elves, if you prefer, who, with a red or green hood, also take care of his reindeer?

The Scandinavian tradition teaches us to distinguish the Ljosalfar (Seelie court), the light elves, who are the good ones who defended the houses from evil spirits, from the Svartalfar (Unseelie court), or dark elves, who are mischievous sprites.

They are fairy beings, especially the light ones are very good and beautiful, they are generally as tall as a three year old child, and have the ability to transform themselves.

But how was it possible that from the mythology of northern Europe these little creatures became part of the world of Santa Claus in the United States during the Victorian era?

Well, it was our inexhaustible writer who first mentioned the elves in literature, which she called the 'Santa Little Helpers'.

During the Summer of 1855 our Louisa May Alcott finished a collection of Christmas stories entitled Christmas Elves.

We read in her correspondence:

Finished fairy book in September. [...] October.– [...] May illustrated my book, and tales called "Christmas Elves." Better than "Flower Fables." Now I must try to sell it.

[Innocent Louisa, to think that a Christmas book could be sold in October.–L. M. A.] 1

This book never saw the light, her publisher didn't agree to sell the aforementioned collection of short stories even in the following December. A few months later May became seriously ill and died. Louisa reacted to the pain of the loss of her beloved sister by taking care of her niece, Louisa May Nieriker, known as Lulu, to whom she dedicated new books of Christmas fairy tales.

The original manuscript, which thus lost its importance, has been lost, but some extracts have been saved in other works of the writer, such as in the poem The Wonders of Santa Claus, published in the magazine HARPER'S WEEKLY in the issue of 26 December 1857, in which was narrated the fervent activity of the helping elves busy in Santa's workshop.

1857 - Harpers weekly : a journal of civilization, [Shenandoah.Iowa: Living History.Inc.] - https://library.si.edu/image-gallery/99827-

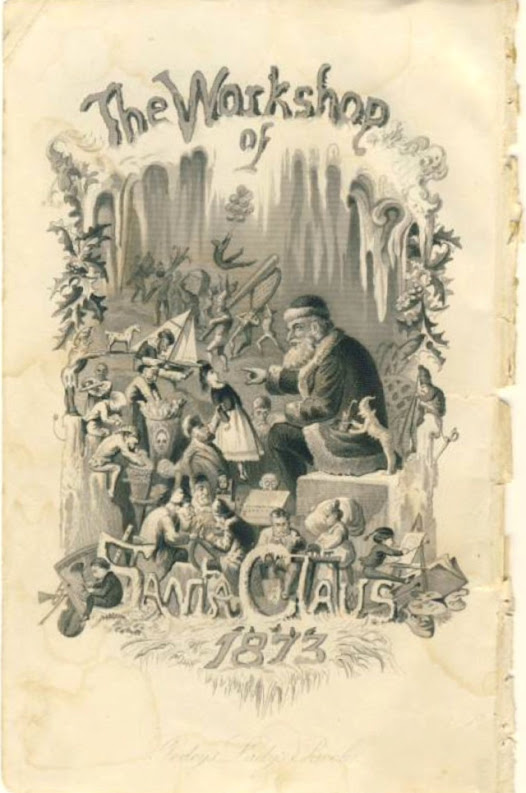

The image of the elves was later popularized by The Godey's Lady's Book, the famous American women's magazine published from 1830 to 1878. The cover illustration of the Christmas issue of 1873 showed Santa Claus surrounded by toys and elves and in the caption that the 'accompanied it read:

"In this way takes place the preparation of toys to be distributed to the little ones in the period before Christmas"

The Godey's Lady's Book magazine played an important role in influencing the Christmas traditions that were developing in the United States during the Victorian period: for example, it was the cover of the 1850 Christmas issue that presented, for the first time, the Christmas tree as we still decorate it today.

And therefore, to conclude, it was thanks to the pen of our Louisa May Alcott and her fervent imagination that we owe the passage of the figure of the elf, belonging for centuries to the Scandinavian mythology, to that of the willing elf who helps Santa Claus to pack his toys: we are therefore also indebted for this too to this authoress who loved Christmas to the point of reinventing its myths and stories in an imagination very personal and filled with phantasy, which still continues to speak to us today.

May this Holiday Season go on filling your home with Joy,

your heart with Love, and your life with laughter.

See you soon ❤

L'eredità natalizia di Louisa May Alcott

- IMMAGINE 1 - Fotografia d'introduzione con un ritratto giovanile di Louisa May Alcott

"Orbene, credo che tutti abbiano ricevuto un dono per Natale e si siano divertiti. Nessuno è stato dimenticato, nemmeno il gatto", disse la signora Ward a sua figlia, mentre guardava Pobbylinda, che, facendo le fusa sul tappeto, con un nuovo nastro intorno al collo, teneva ciò che rimaneva di un osso di pollo tra le zampe.

Era molto tardi, perché l'albero di Natale era stato spogliato, i piccoli erano a letto, i cesti ed i fagotti erano stati lasciati alle porte dei vicini più poveri e tutto era pronto per il felice giorno che sarebbe iniziato quando l'orologio avrebbe suonato le dodici. Tutti stavano riposando dopo le loro fatiche, mentre il ceppo di Natale continuava ad ardere...

Louisa May Alcott, Rosa's Tale, da: Aunt Jo's Scrap-Bag, Volume 5, 1879

Quest'oggi desidero trattare di un argomento speciale.

Voglio parlarvi di un'autrice che tutti noi conosciamo ed abbiamo imparato ad amare nel corso degli anni attraverso le numerose letture che ci ha lasciato in eredità: Louisa May Alcott.

La sua voce, come quella di Charles Dickens, che tanto amava ed ammirava, non conosce mode, non la fermano le barriere del tempo e continua a risuonare inesorabile e a fare l'atmosfera di questi giorni ricchi di magia e di profondi significati, poiché la passione che ella nutriva per le festività natalizie non conosceva davvero limiti.

Il Natale le ispirò infatti numerose storie, fiabe e racconti.

E non è di certo un caso che il suo celeberrimo romanzo Piccole Donne, quello che la consacrò al successo, prenda avvio proprio da una mattina di Natale, un Natale particolare, non solo perché senza doni, ma perché si caricherà di princìpi più veri ed autentici che il cuore di un buon cristiano fa propri ed osserva senza compiere alcuno sforzo: l'amore per il prossimo, la carità, la rinuncia per chi soffre, il calore della famiglia sono i valori che più gratificano, specialmente nel periodo natalizio, che gli conferiscono senso e spessore più di un dono da scartare che magari entusiasma, ma il cui prestigio si esaurisce in qualcosa di meramente materiale.

Ma in realtà non è di questo che intendevo parlarvi oggi, o meglio, non era mia intenzione trattarne in questo modo... ci tengo qui a dirvi di come Louisa May Alcott contribuì a fare del Natale che ancora oggi festeggiamo il vero Natale.

Riuscite ad immaginare un Babbo Natale che prepara i doni senza l'aiuto dei suoi fedeli, operosi ed instancabili folletti od elfi, se preferite, che, con il cappuccio rosso o verde si prendono inoltre cura delle sue renne?

La tradizione scandinava ci insegna a distinguere i Ljosalfar (Seelie court in inglese), gli elfi chiari, che sono quelli buoni che difendevano le case dagli spiriti malvagi, dagli Svartalfar (Unseelie court in inglese), ovvero elfi scuri, che sono spiritelli dispettosi.

Essi sono esseri fatati, in modo particolare quelli chiari sono molto buoni e belli, sono alti generalmente come una bimbo di tre anni, e hanno la capacità di trasformarsi.

Ma come è stato possibile che dalla mitologia del nord Europa queste piccole creature entrassero a far parte del mondo di Babbo Natale negli Stati Uniti durante l'epoca vittoriana?

Ebbene, fu proprio la nostra inesauribile scrittrice la prima a nominare in letteratura gli elfi, che definì i 'Santa Little Helpers', gli Aiutanti di Babbo Natale.

Durante l’estate del 1855 la Alcott terminò una raccolta di racconti natalizi intitolata Christmas Elves, Gli Elfi di Natale.

Leggiamo nel suo epistolario:

Finito il libro di fate a Settembre. [...] Ottobre. [...] May ha fatto le illustrazioni del mio libro di racconti intitolato Christmas Elves. È migliore di Flowers Fable. Ora devo cercare di venderlo. [Quanto sei ingenua Louisa a pensare che un libro natalizio possa essere venduto ad ottobre.–L. M. A.]1

Questo libro non vide mai la luce, il suo editore non accettò di vendere la suddetta raccolta di racconti neppure nel dicembre successivo. Alcuni mesi dopo May si ammalò gravemente e morì. Alcott reagì al dolore per la perdita della sorella occupandosi della nipote, Louisa May Nieriker, detta Lulù cui dedicò nuovi libri di favole natalizie.

Il manoscritto originale, che perse, così, di importanza, è andato perduto, ma se ne sono salvati taluni estratti in altre opere della scrittrice, come nel poema The Wonders of Santa Claus, pubblicato sulla rivista HARPER'S WEEKLY nel numero del 26 dicembre 1857, in cui veniva narrata la fervente attività degli elfi aiutanti affaccendati nel laboratorio di Babbo Natale.

- IMMAGINE 2 - 1857 - Harpers weekly : a journal of civilization, [Shenandoah.Iowa: Living History.Inc.] - https://library.si.edu/image-gallery/99827-

L’immagine degli elfi fu in seguito resa popolare da The Godey’s Lady’s Book, la celeberrima rivista femminile americana pubblicata dal 1830 al 1878. L’illustrazione di copertina del numero natalizio del 1873 mostrava Babbo Natale circondato da giocattoli ed elfi e nella didascalia che l'accompagnava si leggeva:

“In questo modo, ha luogo la preparazione dei giocattoli da distribuire ai piccoli nel periodo che precede il Natale”

- IMMGINE 3 - Copertina del numero natalizio del 1873 di The Godey’s Lady’s Book

La rivista The Godey’s Lady’s Book giocò un ruolo importante nell’influenzare le tradizioni natalizie che si stavano sviluppando negli Stati Uniti durante il periodo vittoriano: per esempio, fu la copertina del numero di Natale del 1850 a presentare, per la prima volta, l'albero di Natale come siamo usi decorarlo ancora oggi.

- IMMAGINE 4 - Copertina del numero natalizio del 1850 di The Godey’s Lady’s Book

E quindi, per concludere, fu grazie alla penna della nostra Louisa May Alcott e alla sua fervida immaginazione che si deve il passaggio della figura del folletto, appartenente da secoli alla mitologia scandinava, a quella dell'elfo volenteroso che aiuta Babbo Natale a confezionare i giocattoli: siamo perciò debitori anche di ciò verso quest'autrice che amò il Natale a tal punto da reinventarne i miti e le storie in un immaginario personalissimo e pieno di fantasia, che ancora oggi continua a parlarci.

Possano queste Feste procedere a colmate le vostre case di Gioia,

il vostro cuore di Amore, e la vostra vita di risate.

A presto ❤

LINKING WITH: