“It can be said that he was the precursor and creator of a very modern social policy, when class collaboration was a myth. He had only one cult in his life: that of work associated with charity. And of the wise purpose of improving the standard of living of his employees he made the essential purpose of his laborious existence. There were two ideals which he particularly directed his work to: the physical and moral well-being of his employees and the education and training of their children. "

(from the obituary for the death of Napoleon Leumann, July 11th, 1930)

The story I'm going to tell you today began in 1831, when Isaac Leumann (1807-1877) moved from Kümmertshausen in Thurgau to Voghera (in Piedmont, Italy), where for a few years he worked as a simple worker in the "Fratelli Tettamanzi" textile factory working flax.

His first son would be born a few month after he decided to take over the company in which he worked; his would be a very important name: he will be called Napoleon.

In the factory worked 105 workers then and it was going to open numerous relationships with the local economic world and with the textile industry.

Within twenty years the "Leumann and son", grew to employ 500 workers and the company successfully participated in the Italian exhibition in Florence which was held during those years, where its production was appreciated by the big names in the sector operating at the time. The turning point for the entrepreneurial destiny of the family came when Napoleon married Amalia Cerutti, daughter of the director and then president of the biggest bank of Voghera, the Cassa di Risparmio, a marriage that wiil ensure considerable and extremely facilitated credits.

With the necessary capital at their disposal, Isaac and Napoleon decided to leave Voghera, a predominantly agricultural town, at the time, and in 1875 they moved to Turin, a city that granted commercial and building favors to entrepreneurs to encourage industrialization and revive their economic fortunes, marred by the move of the capital of Italy to Florence. A plot of land is chosen in the Collegno area along the border with Grugliasco, in a position that allowed easy forwarding of the products to Genoa, from where it was possible to ship them both to the East (especially India) and America.

And the processing will go from that of flax to that of cotton.

The construction of the cotton mill began in the same year with some annexed structures (medical clinic, washhouse, refectory, kindergarten) and went into full operation in the early months of 1877 with good turnover and sure prospects for growth.

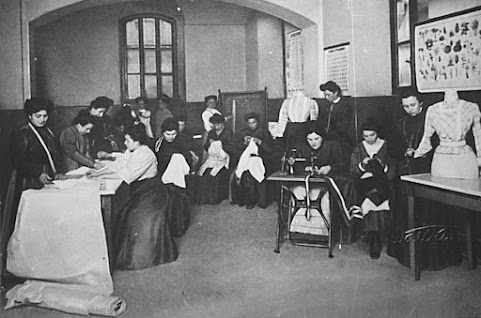

Women working at the Leumann Cotton Mill

The weaving, dyeing and finishing processes were carried out in the Leumann Cotton Mill. The factory was active at full capacity for almost a century.

With the passing of Isaac, in 1887, Napoleon, who inherited from his father the open mind, the propensity for progressivism and the sensitivity towards social issues, gave life to his most famous project, for which he is still remembered today more than for his fruitful entrepreneurial life. To meet the needs of his workers, give them a decent home and all the services and comforts they could need, he launched the project for a workers' village to be built on the sides of the factory.

The Leumann Village with, at the center, the Leumann Cotton Mill

The complex, built between 1875 and 1912, inspired by the building tradition of northern Italy of the time, contaminated above all in the volumetric cuts of the roofs with stylistic features of Swiss origin-given Napoleon's roots, consisted of two residential areas on the sides of the cotton mill, extending for about 60,000 square meters and originally housed about a thousand people including workers, employees and their families. It still includes 59 small villas and houses divided into 120 lodgings, each provided from the beginning with attached toilets and a shared garden on the ground floor.

The buildings necessary for a small community were also gradually built around the houses, namely: the elementary school, a gym, public bathrooms, a food cooperative, a small railway station, a hotel and the Boarding School for Young Female Workers.

It is worth to say that, despite being of Calvinist religion, Napoleon Leumann wanted to equip his village with a church and in 1907 commissioned the project to engineer Pietro Fenoglio.

It is dedicated to Saint Elizabeth and is one of the very few churches in the world, perhaps the only one, built in Art Nouveau style, while also showing some eclectic stylistic elements.

The church with the facing little square in a vintage photograph

In addition, inside the factory, there was a canteen but also a clinic, a nursery, a post office and a sports club.

In 1903 Napoleon decided to made build a small station, called 'La Stazionetta' (The Little Station), placed in front of the entrance to the cotton mill to allow commuter workers to reach the workplace more easily. It was a small wooden building surrounded on three sides by a small portico the interiors of which consisted originally of a single room used as a ticket office and waiting room.

La Stazionetta

Napoleon Leumann was firmly convinced that a correct education was one of the founding elements for having good workers in the future and so, also in 1903, the Leumann Village had its school. Located on the western area of the village: it included six elementary classes on the first floor, while on the ground floor there was the Wera Kindergarten, dedicated to the memory of his daughter who died at an early age.

The school was attended by the children of the workers and of the employees of the cotton mill but also by some residents of Collegno, since it was the only nearby school then existing in the municipality. The school provided free textbooks and could make use of the most advanced teaching equipment and methods of the time. There was also a well-stocked library. In addition, to stimulate the commitment of schoolchildren, Leumann periodically organized awards that included gifts or small bequests in money that was credited to postal books. Particular attention was also given to physical activity with gymnastics practiced daily in the courtyard or in the adjacent gym, including assistance from the doctor of the nearby cotton mill.

In March 1906, evening courses for workers were also activated and, given the concrete results achieved in the didactic field, the school was declared a non-profit organization by Royal Decree. In 1910 the school building was enlarged with the raising of a further floor to house two more classrooms and services. The following year, a report by the Royal School Inspectorate judged the Leumann Village school as a model of education and manners responding in all respects to the real needs of a working class. Subsequently, the school hosted only the elementary classes and the kindergarten was moved to another location.

Despite the cotton mill, after facing a serious crisis in the textile sector during the seventies, found itself ceasing its activity, the village is currently still inhabited by some former employees of the Leumann Cotton Mill-they're about a hundred families. A recent restoration has renewed the most characteristic Art Nouveau structures of the village to their original glory, such as some buildings of the former factory, the former elementary school and La Stazionetta.

In the hope you've enjoyed the topic we dealt with today,

I'm thanking you sincerely

See you soon ❤

IMMAGINE 1- Il Villaggio Leumann in una cartolina d'epoca

«Si può dire che sia stato il precursore e l'ideatore di una politica sociale molto moderna, quando la collaborazione di classe era un mito. Aveva un solo culto nella sua vita: quello del lavoro legato alla carità. E del saggio scopo di migliorare il tenore di vita dei suoi dipendenti fece lo scopo essenziale della sua laboriosa esistenza. Due erano gli ideali a cui indirizzava in modo particolare il suo lavoro: il benessere fisico e morale dei suoi dipendenti e l'educazione e la formazione dei loro figli. "

(dal necrologio coniato in occasione della morte di Napoleone Leumann

l'11 luglio 1930)

La storia che vi racconterò oggi inizia nel 1831, quando Isaac Leumann (1807-1877) si trasferì da Kümmertshausen in Turgovia a Voghera, in Piemonte, dove per alcuni anni lavorò come semplice operaio nella fabbrica tessile " Fratelli Tettamanzi" addetta alla lavorazione del lino.

Il suo primo figlio sarebbe nato pochi mesi dopo che egli decise di rilevare l'azienda in cui lavorava; il suo era sarà un nome importantissimo: si chiamerà Napoleone.

Nella fabbrica lavoravano allora 105 operai e si sarebbero aperti numerosi rapporti con il mondo economico locale e con l'industria tessile italiana.

Nel giro di vent'anni la "Leumann e figlio" crebbe fino ad occupare 500 dipendenti.

L'azienda partecipò con successo alla fiera italiana di Firenze che si tenne durante quegli anni, dove la sua produzione fu apprezzata dai grandi nomi del settore operanti all'epoca. La svolta per il destino imprenditoriale della famiglia arrivò quando Napoleone sposò Amalia Cerutti, figlia del direttore e poi presidente della più grande banca di Voghera, la Cassa di Risparmio, un matrimonio che assicurò crediti considerevoli ed estremamente agevolati.

Con i capitali necessari a disposizione, Isacco e Napoleone decisero di lasciare Voghera, all'epoca centro prevalentemente agricolo, e nel 1875 si trasferirono a Torino, città che concedeva favori commerciali ed edilizi agli imprenditori per agevolare l'industrializzazione e rilanciare le loro fortune economiche, intaccate dal trasferimento della capitale d'Italia a Firenze. Venne scelto un appezzamento di terreno nel territorio di Collegno, lungo il confine con Grugliasco, in una posizione che permetteva di spedire agevolmente i prodotti a Genova, da dove era possibile inviarli sia in Oriente (soprattutto in India) che in America.

E la lavorazione tessile passò da quella del lino a quella del cotone.

Nello stesso anno iniziò la costruzione del cotonificio con alcune strutture annesse (ambulatorio medico, lavatoio, mensa, asilo nido) ed entrò a regime nei primi mesi del 1877 con un buon fatturato e sicure prospettive di crescita.

IMMAGINE 2 - Donne lavoratrici nel Cotonificio Leumann

I processi di tessitura, tintura e finissaggio venivano tutti eseguiti nel cotonificio Leumann che rimase attivo a pieno regime per quasi un secolo.

Con la morte di Isaac, nel 1887, Napoleone, che ereditò dal padre la mentalità aperta, la propensione al progressismo e la sensibilità per le questioni sociali, diede vita al suo progetto più famoso, per il quale è ancora oggi ricordato più che per la sua fertile attività imprenditoriale. Per soddisfare i bisogni dei suoi lavoratori, dare loro una casa dignitosa e tutti i servizi e le comodità di cui potevano necessitare, egli si fece promotore di un progetto per la costruzione di un villaggio operaio da edificare ai lati della fabbrica.

IMMAGINE 3 - Il Villaggio Leumann con, al centro, il cotonificio

Il complesso, edificato tra il 1875 e il 1912, ispirato alla tradizione edilizia del nord Italia dell'epoca e contaminato soprattutto nei tagli volumetrici dei tetti da stilemi di origine svizzera-date le origini d'oltralpe di Napoleone-si compone di due nuclei abitativi siti ai lati del cotonificio: esso si estende per circa 60.000 mq e ospitava in origine circa un migliaio di persone tra operai, impiegati e le loro famiglie. Comprende ancora 59 villini e casette suddivise in 120 alloggi, ciascuno dotato fin dall'inizio di annessi servizi igienici e giardino condominiale al piano terra.

IMMAGINI 4-5-6-7- Le villette del Villaggio Leumann: i dettagli architettonici più significativi e gli interni

Intorno alle case si costruirono progressivamente anche gli edifici necessari per una piccola comunità, ovvero: la scuola elementare, una palestra, i bagni pubblici, una cooperativa alimentare, una piccola stazione ferroviaria, un albergo, il Convitto per Giovani Lavoratrici e una chiesa.

Vale la pena di dire che, pur essendo di religione calvinista, Napoleone Leumann volle dotare il suo villaggio di una chiesa e nel 1907 ne commissionò il progetto all'ingegner Pietro Fenoglio.

È dedicata a Santa Elisabetta ed è una delle pochissime chiese al mondo, forse l'unica, costruita in stile liberty, pur mostrando alcuni stilemi eclettici.

IMMAGINE 8 - La chiesa con la piazzetta prospiciente in una fotografia d'epoca

Inoltre, all'interno dello stabilimento, c'era una mensa ma anche un ambulatorio, un asilo nido, un ufficio postale e una società sportiva.

Nel 1903 Napoleone decise di far costruire una piccola stazione, denominata 'La Stazionetta', posta davanti all'ingresso del cotonificio per consentire ai lavoratori pendolari di raggiungere più facilmente il luogo di lavoro. Si trattava di un piccolo edificio in legno circondato su tre lati da un porticato i cui interni erano originariamente costituiti da un unico ambiente adibito a biglietteria e sala d'attesa.

IMMAGINE 9 - La Stazionetta

Napoleone Leumann era fermamente convinto che una corretta educazione fosse uno degli elementi fondanti per avere in futuro buoni lavoratori e così, sempre nel 1903, il Villaggio Leumann ebbe la sua scuola. Situato nel quartiere occidentale del paese, l'edificio comprendeva al primo piano sei classi elementari, mentre al piano terra si trovava l'Asilo Wera, dedicato alla memoria della figlia morta in tenera età.

La scuola era frequentata dai figli degli operai e dei dipendenti del cotonificio ma anche da alcuni residenti di Collegno, essendo l'unica scuola vicina allora esistente nel comune. La scuola provvedeva a procurare libri di testo gratuiti, comprendeva una biblioteca ben fornita e poteva utilizzare le attrezzature ed i metodi didattici più avanzati dell'epoca. Inoltre, per stimolare l'impegno degli scolari, Leumann organizzava periodicamente competizioni che comportavano doni o piccoli lasciti in denaro che venivano accreditati su libretti postali. Particolare attenzione veniva dedicata anche all'attività fisica con ginnastica praticata quotidianamente nel cortile o nell'adiacente palestra, ed era compresa l'assistenza del medico del vicino cotonificio.

Nel marzo del 1906 furono attivati anche i corsi serali per operai e, visti i concreti risultati raggiunti in ambito didattico, la scuola fu dichiarata Onlus con Regio Decreto. Nel 1910 l'edificio scolastico fu ampliato con l'innalzamento di un ulteriore piano per ospitare altre due aule e servizi. L'anno successivo, un rapporto del Regio Ispettorato dell'Istruzione giudicò la scuola del Villaggio Leumann un modello di educazione e di buone maniere rispondente, a tutti gli effetti, ai reali bisogni di una classe operaia. Successivamente la scuola ospiterà solo le classi elementari e l'asilo verrà spostato in altra sede.

Nonostante il cotonificio, dopo aver affrontato una grave crisi del settore tessile negli anni settanta, si sia trovato a cessare la propria attività, il villaggio è attualmente ancora abitato da alcuni ex dipendenti del Cotonificio Leumann-si tratta di un centinaio di famiglie. Un recente restauro ha riportato all'antico splendore le strutture liberty più caratteristiche del villaggio, come alcuni edifici dell'ex fabbrica, l'ex scuola elementare e La Stazionetta.

IMMAGINE 10 - Napoleone Leumann

Nella speranza che l'argomento di cui ~

My little old world ~ ha trattato oggi

Vi sia stato gradito,

Vi ringraziando sentitamente

A presto ❤

LINKING WITH: