“The number of visitors reported to have visited the cemeteries were very large (10,000 to the new cemetery in Cardiff in 1879, 20,000 in 1889 and 50,000 in 1898; 25,000 to Swansea cemetery in 1906). There were problems with crowd control resulting in the need for extra police or the distribution of tickets only to those visiting relatives’ graves. The demand for flowers for this custom was so great that they were sent from London.”

Welcome to all of you inside my little corner where enjoying gardening, home, poetry, leisure, painting and history for a romantic encounter with the past that makes us dream.

martedì 28 marzo 2023

⊰ Victorian Spring and Easter Traditions ⊱

“The number of visitors reported to have visited the cemeteries were very large (10,000 to the new cemetery in Cardiff in 1879, 20,000 in 1889 and 50,000 in 1898; 25,000 to Swansea cemetery in 1906). There were problems with crowd control resulting in the need for extra police or the distribution of tickets only to those visiting relatives’ graves. The demand for flowers for this custom was so great that they were sent from London.”

mercoledì 22 marzo 2023

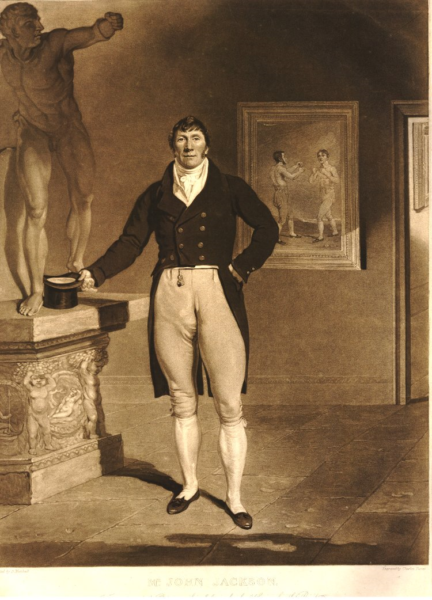

Boxing with Byron

LORD BYRON SPARRING WITH JOE "GENTLEMAN" JACKSON

How many things did Lord George Byron do in his, albeit short, life?

We have met him several times during our walks through History and we can say, without any doubt, that he really did many things, apparently different and almost conflicting with each other. Byron was a poet, playwright, adventurer, wanderer, Dandy, Bohemian, revolutionary... But few people know that Byron also embarked on the path of boxing. His was the great era of the boxer when they still fought down the streets and the prize was in money. The fights took place with bare fists and often lasted for hours. They consisted of a single round that ended only when one of the two boxers was rejected or thrown to the ground! In those years the boxer John Jackson – commonly known as “Gentleman” Jackson – was almost as famous as the Duke of Wellington. He was Champion of England from 1795 to 1803, then, after his retirement, he began to train students athletically, including, precisely, the young Byron. Indeed, many noble young men took lessons from Jackson at his school on London's Bond Street.

"To day I have been very sulky – but an hour’s exercise with Mr. Jackson of pugilistic memory – has given me spirits & fatigued me into that state of languid laziness which I prefer to all other." (Lord Byron, letter 8th April 1814)

Sports reporter Pierce Egan, editor of Boxiana magazine, among other things, who followed London sports and Byron's ardent admirer wrote:

"His Lordship of him always entered into the spirit of the thing, as into his poetry; – regarded boxing as a national proclivity – a stimulus to true courage… In putting a… he received coolly from his opponent, and returned to his opponent with all the vigor and assurance of a master of the art." (Book of Sports)

Throwing oneself "into the spirit of the thing" is the cardinal element here, the hard training affording Byron a physical and psychological outlet: Byron's absorption in vigorous exercise may simply have been an attempt to reconcile his conscience for the behavior not entirely blameless past and present. Meanwhile he continued to record in his diary:

"The more violent the fatigue, the better my mood will be for the rest of the day; and then my evenings have that calm nothing of languor, which delights me most."

giovedì 16 marzo 2023

Irish linen and Victorian "spinsters"

First of all, I would like to clarify the use of the word SPINSTER in order to avoid any kind of misunderstanding, due to the derogatory connotation it has assumed over time. Literally, SPINSTER is a woman who drives the spinning wheel, a WHEEL SPINNER WOMAN.

The term SPINSTER was later used to define a woman who was unmarried or advanced in age - again in the context of the time - and who had no expectations of marrying. Over time it became an offensive and even abusive term, meaning a middle-aged or elderly woman, unmarried and with a harsh or sad character, depending on the circumstances in which she was presented.

Having clarified the meaning of this word, My little old world dedicates St. Patrick's Day to all Irish women who were the promoters of an artisan craft that has survived over the centuries, leaving examples of minor but no less beautiful or less precious artistic manifestations.

domenica 5 marzo 2023

Amos Bronson Alcott, Abigail May and Orchard House, Little Women's 'nest'

Surely, dear father, some good angel or elf dropped a talisman in your cradle that gave you force to walk thro life in quiet sunshine while others groped in the dark...

~ Louisa May Alcott to her father

November 28, 1855

In 1857, Amos Bronson Alcott purchased 12 acres of land with a manor house that had been on the property since the 1660s for $945. He then moved a small tenant farmhouse and joined it to the rear of the larger house, making many improvements over the course of the next year, as he detailed in his journals. The grounds also contained an orchard of 40 apple trees which greatly appealed to Mr. Alcott, who considered apples the most perfect food. It is not surprising, then, that he should name his home "Orchard House".

Abba’s love for her visionary husband was a mainstay in calm and storm. Although frequently frustrated by his inability to support his family, Mrs. Alcott believed in her husband and his ideals -- even when it seemed that the rest of the world did not. She wrote in her journal that she could never live without him:

Abba sitting on an armchair in his husband's study at Orchard House

And here's the study as you can see it today by visiting Orchard House

Amos Bronson Alcott, Abigail May e Orchard House, il 'nido' di Piccole donne

Per certo, mio caro Padre, qualche angelo buono o qualche elfo ha lasciato cadere nella tua culla un talismano che ti ha dato la forza di camminare nella calma della luce del sole, mentre altri brancolavano nel buio...

~ Louisa May Alcott a suo padre

28 novembre 1855

Immagine 1 - DISEGNO DI ORCHARD HOUSE

Dopo aver cambiato dimore per più di venti volte in quasi trent'anni, gli Alcott avevano finalmente trovato il loro posto di ancoraggio a Orchard House, dove vissero fino al 1877. Amos Bronson Alcott era nato il 29 novembre 1799. Figlio di un coltivatore di lino di Wolcott, Connecticut, imparò da solo a leggere e a scrivere utilizzando un carboncino ed un pavimento di legno. Attraverso la pura forza di volontà e la dedizione agli ideali, si è formato e ha guidato il suo genio ad esprimere la sua vocazione: quella di educatore progressista e leader dei Trascendentalisti.

"Trascendentalismo" era un termine coniato da un movimento di scrittori e pensatori del New England negli anni '30 del XIX° secolo. Costoro credevano che le persone nascessero buone, che possedessero un potere chiamato intuizione e che potessero avvicinarsi a Dio attraverso la Natura. Amos Bronson Alcott fu l'unico ad aver fatto propri anche nella sua vita i principi trascendentalisti. Da giovane aveva lavorato come tuttofare e giardiniere. Quando Orchard House divenne la sua casa, era sposato con Abigail May da 27 anni. Abigail, o Abba come veniva chiamata, aveva un temperamento appassionato, una mente fine e un cuore generoso. Avvertiva profondamente le ingiustizie del mondo e lavorò energicamente per sostenere varie cause, specialmente quelle volte ad aiutare i poveri o che promuovevano l'abolizione della schiavitù, quelle che patrocinavano i diritti delle donne e valutavano la temperanza, ecco perché ha ispirato il personaggio di Marmee in Piccole donne. Abba incontrò Amos Bronson Alcott a Brooklyn, nel Connecticut, a casa di suo fratello, Samuel Joseph May, che fu il primo ministro unitario dello stato. Durante il loro lungo corteggiamento, Mr. Alcott, "un amante timido", comunicava i suoi sentimenti a Miss May lasciandole leggere i passaggi che scriveva su di lei nel suo diario. Bronson e Abba si sposarono nella King's Chapel di Boston il 23 maggio 1830.

L'amore di Abba per il marito visionario era un pilastro nella calma e nella tempesta. Sebbene spesso frustrata dalla sua incapacità di mantenere la sua famiglia, Mrs. Alcott credeva in suo marito e nei suoi ideali, anche quando sembrava che il resto del mondo non lo facesse. Su legge nel suo diario che non avrebbe mai potuto vivere senza di lui:

"Penso di poter più facilmente imparare a vivere senza fiato."

Dal loro matrimonio nacquero quattro figlie: Anna, Louisa, Lizzie e May.

Immagine 7 - IL SOTTOTETTO

Immagine 8 - LA CUCINA

Immagine 9 - VEDUTA DELLA SALA DA PRANZO

Immagine 10 - IL SALOTTO DECORATO PER NATALE (RICORDERETE SICURAMENTE CHE IL ROMANZO INIZIA IN UNA MATTINA DI NATALE PIUTTOSTO SQUALLIDA DI UN ANNO COMPRESO TRA IL 1863 E IL 1866, CHE CORRISPONDE ALL'ULTIMA PARTE DELLA GUERRA DI SECESSIONE)

Immagine 11 - E INFINE ORCHARD HOUSE VISTA DALL' ESTERNO, CON IL CAMINO FUMANTE, COME SAREBBE IN UNA FREDDA GIORNATA INVERNALE COME OGGI!

Con queste meravigliose immagini che suggeriscono che ancora ci sia vita in quei luoghi, sembra di aver compiuto un salto indietro nel tempo, che ne dite?

.jpg)

,%201874.jpg)

.jpg)

%20Kittens%20on%20a%20Spinning%20Wheel,.jpg)